Split Countries

The uneven nature of the spread of the gospel brings opportunity and challenge

As Missio Nexus ventures further into the realm of the A Third of Us I have been musing a bit more on why the unreached continue to be such a challenge to the global missions movement. I was recently thinking about the challenge of “split countries” which give us a unique window into some of these challenges.

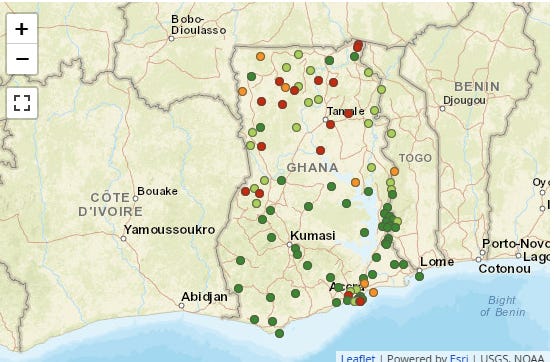

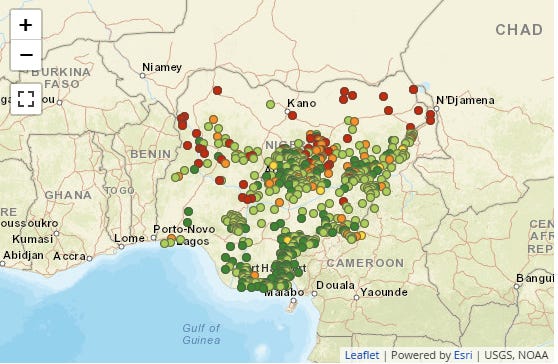

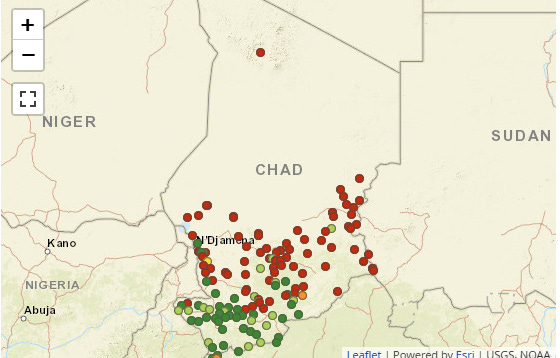

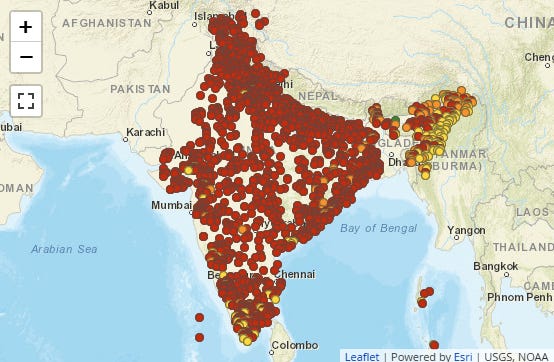

A “split country” is one in which the unreached cultures are geographically concentrated in one part of the country, while Christianity is dominant in another part of the country. There are numerous examples of split countries along a geographic line which cuts across Africa. Here are a few examples, with maps screenshotted from The Joshua Project. I chose these places because I have traveled to the unreached sections of each of these countries but there are other examples as well.

Ghana - The Christianized southern part of the country reflects the coastal strategies of a previous centuries’ missionary work. If you were to visit the south, you would find a robust missions movement. Going to the north, the situation changes substantially, and you find Muslim populations.

Nigeria - Nigeria is the quintessential split country. Hard core Islamic populations in the north are waging a terror war against the largely Christian population of the south. Nigeria has a maturing, well led missionary movement. I think this is one of the bright spots in African missions. Yet, the stark and aggressive Islamic cultures make for tough sledding for missionaries. The dominant group is the Hausa-Fulani and they are unreached, with small pockets of work here and there.

Chad - Early missionary work in Chad focused on the peoples that live in the southern-most region. Then there is a large cluster of unreached above them, then a less populated but heavily Islamic region in the north.

This phenomenon is not limited Africa, though. Nagaland, in eastern India, is the most Christianized region of the country by far. Southern India is home to a substantial church as well. Yet, in the north, large Islamic populations are mixed with Hindu people groups, forming perhaps the biggest geographic missions challenge of our day. This geographic concentration means that Indian missionaries cross significant cultural barriers as they move from one region of the country to another.

Split countries provide us with a set of opportunities and challenges. “Culturally near” missions is a strategy that should be a part of any team’s overall approach. Certainly, among people group clusters with shared elements of language and culture, this makes sense. In culturally distant but geographically close situations more regionalized missions efforts have worked. Brazilian missionaries, for example, have proven effective at reaching Amazon tribes.

However, we also need to see the limits of culturally near missionaries, too. Often, culturally and geographically near missionaries have to overcome hurdles outsiders do not. A Han Chinese might face suspicion in Tibetan areas due to historical tensions, even more so than a foreigner’s outsider status might confer. A missionary from Nagaland would not have the same cultural status in Northern India as an outsider might. Shared nationality doesn’t erase biases, prejudice, or historical realities.

Split countries highlight the need for partnership between culturally (or perhaps, geographically) near missionaries and foreign/outside missionaries. In this day and age, where the emphasis is on indigenous missions, it is good to pause and think about the unique contribution that outsiders bring. The roles may need to change, but the reality is that we all need each other. The stakes are too high for us to think simplistically about how we might see the gospel spread in difficult areas.